Wood is Wonderful

Isn’t it, though? One log can make an almost infinite array of looks based on where in the log it came from and what the orientation of that log was when it was sawn. Here we will give a brief overview of the three primary types of cut, and how they affect the look of the board they produce.

Plainsawn

This type of cut is the most common in the modern (last 100 years or so) era of sawmilling. For the most part, after the log is squared up, slabs are taken off the outside in the most efficient manner as to produce the greatest quantity of material. This generally results in boards with a “cathedral” or “landscape” pattern of grain created from the annual rings in the log.

Quartersawn

There are a few different ways of producing quartersawn lumber, but for the purposes of this post we will stick to the one that gave this cut its name. To put it simply, the whole log is first cut into Quarters, then those sections are rotated 45° and the boards are cut vertically out of those pieces. This results in boards where the grain is generally perpendicular to the face of the board, resulting in a pattern of mostly straight, narrowly separated lines of grain. There are two main reasons for cutting logs this way.

Stability

Quartersawn lumber is inherently more stable than Plainsawn lumber. The reason is that all wood moves as it takes on and releases moisture. This happens even with properly kiln-dried lumber due to seasonal changes in Relative Humidity. The problem is that almost no species moves the same amount radially and tangentially as those changes occur. The movement Radially is often half as much as it is Tangentially. We’ve got some pics to help explain, but in English, a Plainsawn board has mostly Tangential grain going across the width whereas a Quartersawn board has mostly Radial grain. This means that a Quartersawn board of the same width as a Plainsawn board will move half as much under the same conditions.

OK, that matters most when you’re making something that uses larger boards, and especially if several or many are joined or butted together, like in a floor or table top. But the other factor is that Plainsawn lumber doesn’t have nice, consistent patterns of the rings. Unfortunately, trees don’t grow like pencils. So from one end of a log to the other there can be a fairly wide variety of grain directions. Put this together with the difference in movement and suddenly your board is not going to be “flat as a board” for long.

Figure

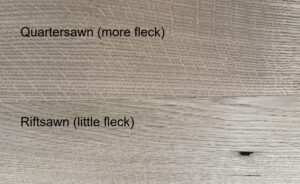

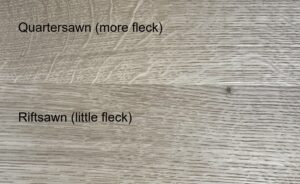

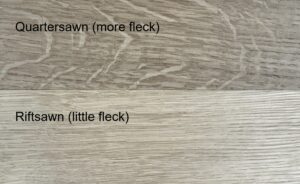

All species have two grain patterns. They are the annual rings – the ones you use to count how old the tree is, and medullary rays. These medullary rays are perpendicular to the annual rings, radiating from the center of the tree out towards the edge. In many species these are invisible to the naked eye, but in others they can vary from “visible” to “prominent”. Of the species we make our picture frame moulding from, they are visible in Cherry and Maple, and prominent in the Oaks, more so in White Oak than Red Oak. These rays are relatively thin, but when exposed side-on they can be very striking. If you’ve ever seen a piece of Craftsman-era oak furniture (for instance a Stickley piece) you have probably seen this effect. Depending on exactly how the grain is oriented in the board, they have been variously described as “fish scales”, “water blotches”, “tiger stripes”. We call them what the are, which is “ray flecks”.

Riftsawn

Riftsawn lumber is a subset of Quartersawn. It is not generally separated in most species because the medullary rays tend not to be very noticeable in most species. However, because of their prominence in the Oaks, there IS a separation. Riftsawn has all the physical benefits of Quartersawn, but here the “quartered” sections are not rotated 45°, more like 30°. This produces lumber that has the straight, narrow grain lines of Quartersawn, but WITHOUT the ray fleck.

What does this mean for our picture frame moulding?

This is where it can get a little confusing, because we use Plainsawn lumber for all our caps and floaters. However, the above described visual effects come into play on the FACE (wide side) of the board. For caps and floaters, the face of the board becomes the SIDE of the moulding, and the EDGE of the board becomes the FACE. The end result is that the face of these profiles ends up with the character of a Quartersawn or Riftsawn board.

Because of the nature of how Plainsawn boards come out of the log, the edge grain is not consistently one pattern or the other. So the bottom line is that these profiles could have either or BOTH patterns within the same stick.

If you or your customer have a strong feeling about one or the other, you can specify “More fleck” or “Less fleck”. There is an additional charge for this, and we will do the best we can, but as you can see from the pictures, even within More or Less there is a significant variation.

Here is another page that talks about and explains where these funky features come from and how they affect the look of the surface.